Barbra Wright has fond memories of her childhood growing up on Kenton Street in Hanford Village.

“I knew every person that lived on this street,” she said. “This was one of the most fun places in the world.”

But her childhood home is no longer there. And her story is not unique.

Hanford Village has moved far from its vibrant history.

The village was founded back in the early 1900s. It had its own mayor, police department and fire department. There were small businesses, churches and a school.

“We had about everything we needed, just a little community village, it was great,” said Richard Bolden, a former resident.

Bolden grew up in a home on Bowman Avenue, where his father still lived until very recently. His father was in the service and, like many others, moved to Hanford Village after World War II.

The community famously attracted Tuskegee Airmen, who were stationed at what was then Lockbourne Air Force Base.

“They had a community of optimism and hope, considering that they were coming out of slavery,” said community historian Rita Fuller-Yates. “Their grandparents normally were slaves. So these were people who touched history but were also wanting to change the trajectory of our past. And so they began building communities so that we could begin changing what it was that we were. We began seeing education in a better light and enhancing the experience of the African-American experience so that we could become better.”

The community had hit its stride and was thriving. But everything changed with the construction of Interstate 70, which sliced right through the community, changing it forever.

“I’ve never seen a community so chopped up into little pieces like Hanford,” said Jack Marchbanks, the director of the Ohio Dept. of Transportation. “It’s sad to behold.”

Marchbanks said decisions about the interstate system were made by those in political power, to the detriment of those who were politically powerless.

In the case of the Hanford Village, that meant a re-direct of the highway around Bexley, instead cutting right through the community that was originally defined by Livingston Avenue, Nelson Road, Main Street and Lilley Avenue.

“When you look at where interstates are routed, they are an exact road map through the communities that lacked the political power to not have them constructed through those communities,” Marchbanks said.

It was an effect felt by all those who lived in the village at the time. Many lost their neighbors and their homes.

In the village’s application to join the National Register of Historic Places, which was granted in 2013, the impact of the interstate construction was noted. One man reportedly set his house on fire.

The uncertainty of whether one's home was in the proposed highway alignment, coupled with practical fears such as pulling children from school and the price offered by the state for one's house, competed with problems caused by segregation. Since there were limited areas in Columbus where African Americans could live and these areas were often the target of urban renewal activities, residents wondered if the next house they purchased would also be taken away by the state. And since these areas were already overcrowded, the question, "Where can I go where they'll allow colored people?" was a typical worry. 91 It has been noted by legal scholars that areas perceived as blighted did not get the same legal protections where eminent domain was involved that more affluent neighbors received at the time. The imminent highway construction shattered lives. A few villagers felt that some residents never recovered from the ordeals the little village suffered.92 One Carver Addition resident was so enraged that his house would be taken by the state that he set it on fire. It was yet another instance where full citizenship was not realized for the residents of Hanford: veterans who had fought for their country in Europe and the Pacific had their homes demolished in the service of a racist sociological theory.

Fuller-Yates noted the one bright spot was that many of the homes themselves were saved and moved elsewhere. But the message being sent to the community was clear.

“So they were obtaining the American dream, and then, here we go again, here we go again as soon as we find our confidence,” she said. “White America normally finds a way to, once again, acknowledge us as people that aren’t worth being a citizen, even of Columbus, Ohio.”

Bolden’s family home is just a few doors down from the cutoff on Bowman, where the homes no longer exist. And instead of the neighbors who once lined the other side of the street, there is a view of the interstate just beyond Alum Creek Drive.

“It hurt for a while, like anything else and any other community that would get destroyed,” he said. “It hurts you for a while, but you know, as a survivor, you learn to adapt and you move on with life.”

And that’s what many neighbors have done. But many more no longer live there and only have the memories they are now trying to preserve.

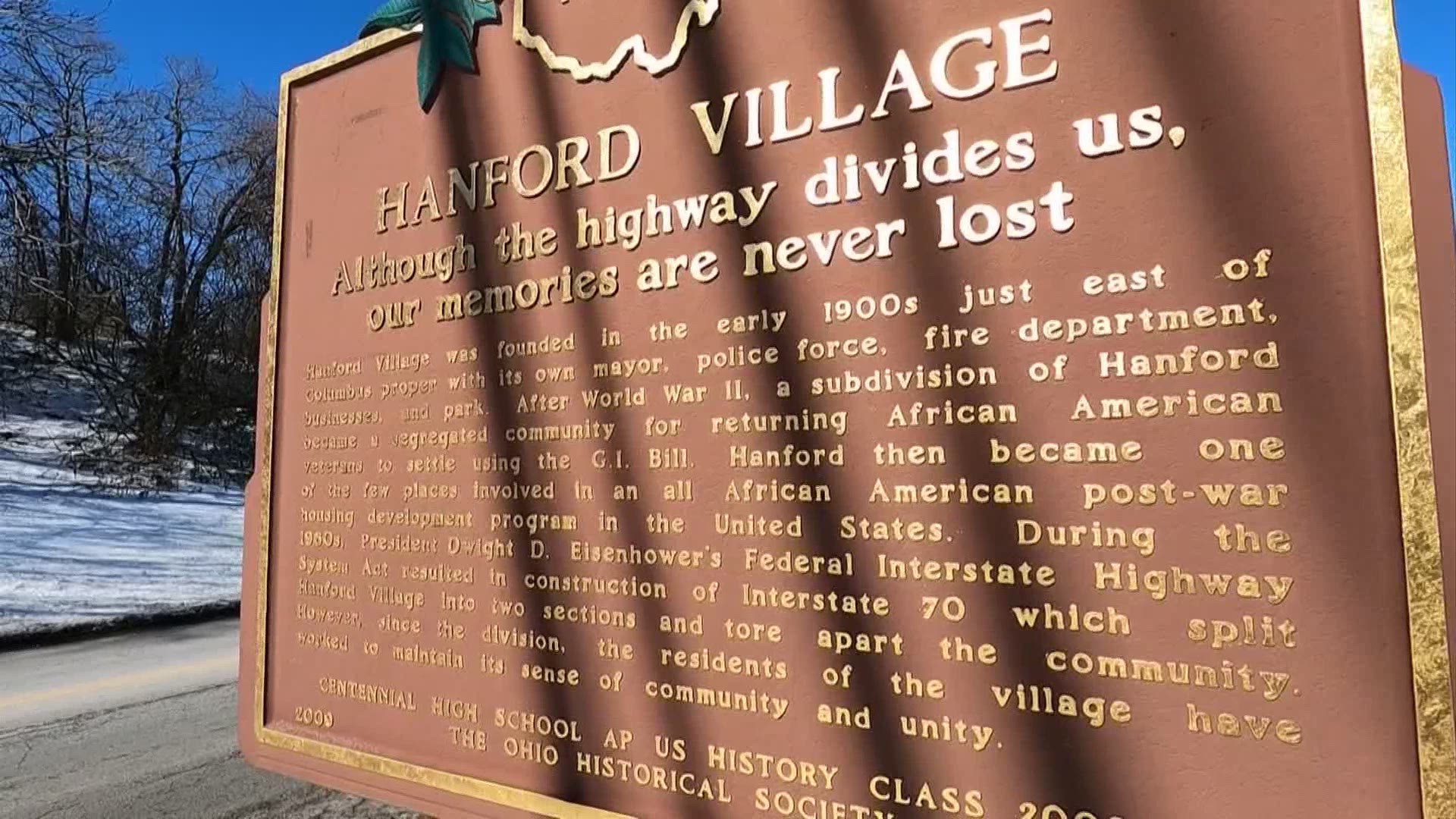

The community is now listed on the national register, and there is an Ohio Historical Marker in place along Nelson. It reads: Although the highway divides us, our memories are never lost.

The storied history of this place is worth remembering and learning from, according to Fuller-Yates.

“How can we preserve what we don’t know is valuable,” she said. “So, learning local Black history, teaching Columbus Black history, has become my mission because we have to own our story so that we can preserve our story. We’re the only ones who can do it.”